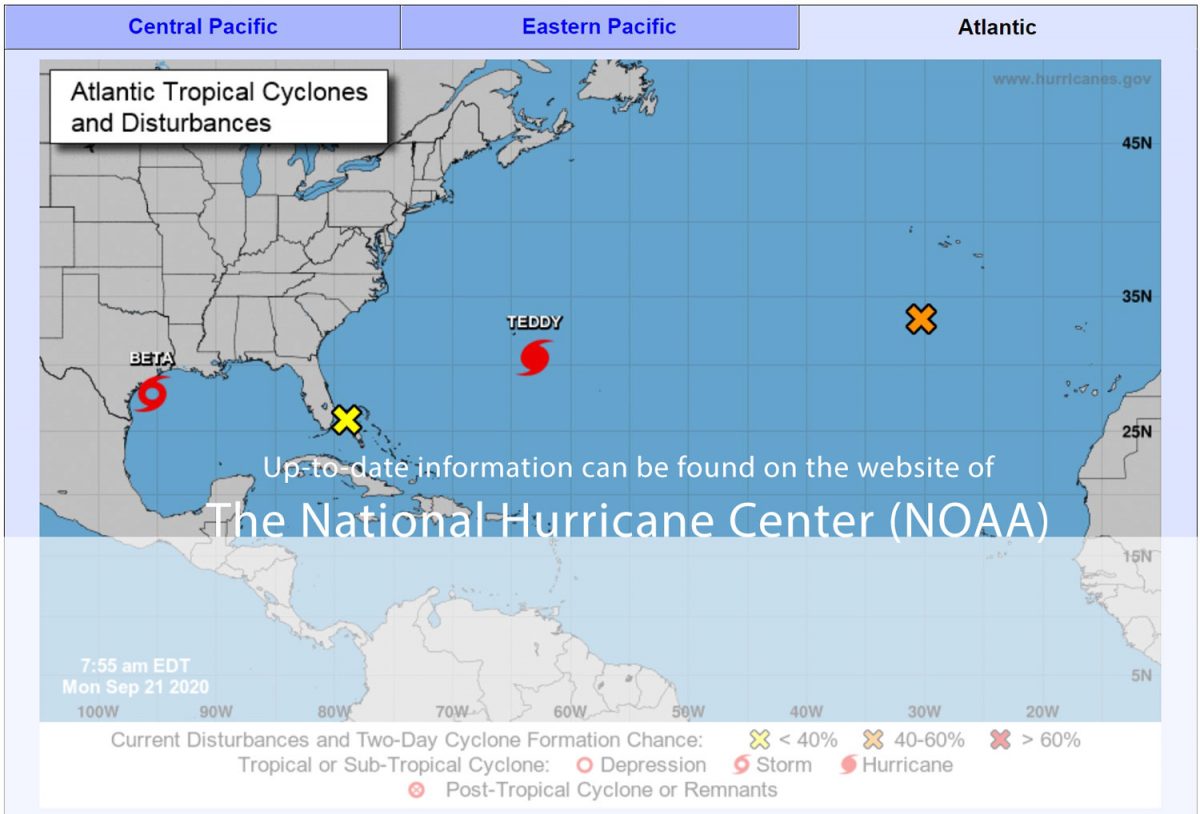

Latest Information

The National Hurricane Center (NOAA) offers the most-up-to-date information on their website: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/

Hurricane Definition, Introduction

A hurricane is a type of tropical cyclone – an organized rotating weather system that develops in the tropics. Hurricanes rotate counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere. Tropical cyclones are classified as follows:

- Tropical Depression

An organized system of persistent clouds and thunderstorms with a closed low-level circulation and maximum sustained winds of 38 mph (33 knots*) or less. - Tropical Storm

An organized system of strong thunderstorms with a well defined circulation and maximum sustained winds of 39 to 73 mph (34-63 knots). - Hurricane

An intense tropical weather system with a well defined circulation and sustained winds of 74 mph (64 knots) or higher. In the western North Pacific, hurricanes are called typhoons, and similar storms in the Indian Ocean are called cyclones.

*NOTES:

A knot is one nautical mile per hour; a nautical mile is about 1.15 statute miles.

Hurricane – where does the name come from?

The term hurricane has its origin in the indigenous religions of old civilizations. The Mayan storm god was named Hunraken. A god considered evil by the Taino people of the Caribbean was called Huracan. Hurricanes may not be considered evil but they are one of nature’s most powerful storms. Their potential for loss of life and destruction of property is tremendous. Those in hurricane-prone areas need to be prepared for hurricanes and tropical storms. Even inland areas, well away from the coastline, can experience destructive winds, tornadoes and floods from tropical storms and hurricanes.

Hurricane classification, Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale is a 1-5 rating based on the hurricane’s present intensity. This is used to give an estimate of the potential property damage and flooding expected along the coast from a hurricane landfall. Wind speed is the determining factor in the scale, as storm surge values are highly dependent on the slope of the continental shelf in the landfall region. Note that all winds are using the U.S. 1-minute average.

Category One Hurricane:

Winds 74-95 mph (64-82 kt or 119-153 km/hr). Storm surge generally 4-5 ft above normal. No real damage to building structures. Damage primarily to unanchored mobile homes, shrubbery, and trees. Some damage to poorly constructed signs. Also, some coastal road flooding and minor pier damage.

Category Two Hurricane:

Winds 96-110 mph (83-95 kt or 154-177 km/hr). Storm surge generally 6-8 feet above normal. Some roofing material, door, and window damage of buildings. Considerable damage to shrubbery and trees with some trees blown down. Considerable damage to mobile homes, poorly constructed signs, and piers. Coastal and low-lying escape routes flood 2-4 hours before arrival of the hurricane center. Small craft in unprotected anchorages break moorings.

Category Three Hurricane:

Winds 111-130 mph (96-113 kt or 178-209 km/hr). Storm surge generally 9-12 ft above normal. Some structural damage to small residences and utility buildings with a minor amount of curtainwall failures. Damage to shrubbery and trees with foliage blown off trees and large trees blown down. Mobile homes and poorly constructed signs are destroyed. Low-lying escape routes are cut by rising water 3-5 hours before arrival of the center of the hurricane. Flooding near the coast destroys smaller structures with larger structures damaged by battering from floating debris. Terrain continuously lower than 5 ft above mean sea level may be flooded inland 8 miles (13 km) or more. Evacuation of low-lying residences with several blocks of the shoreline may be required.

Category Four Hurricane:

Winds 131-155 mph (114-135 kt or 210-249 km/hr). Storm surge generally 13-18 ft above normal. More extensive curtainwall failures with some complete roof structure failures on small residences. Shrubs, trees, and all signs are blown down. Complete destruction of mobile homes. Extensive damage to doors and windows. Low-lying escape routes may be cut by rising water 3-5 hours before arrival of the center of the hurricane. Major damage to lower floors of structures near the shore. Terrain lower than 10 ft above sea level may be flooded requiring massive evacuation of residential areas as far inland as 6 miles (10 km).

Category Five Hurricane:

Winds greater than 155 mph (135 kt or 249 km/hr). Storm surge generally greater than 18 ft above normal. Complete roof failure on many residences and industrial buildings. Some complete building failures with small utility buildings blown over or away. All shrubs, trees, and signs blown down. Complete destructon of mobile homes. Severe and extensive window and door damage. Low-lying escape routes are cut by rising water 3-5 hours before arrival of the center of the hurricane. Major damage to lower floors of all structures located less than 15 ft above sea level and within 500 yards of the shoreline. Massive evacuation of residential areas on low ground within 5-10 miles (8-16 km) of the shoreline may be required.

Who was who?

These are just some examples, the list is not meant to be complete. You will most likely remember the names of the major Cat 5 storms in our list…

Category 1:

Hurricanes Allison of 1995 and Danny of 1997 were Category One hurricanes at peak intensity.

Category 2:

Hurricane Bonnie of 1998 was a Category Two hurricane when it hit the North Carolina coast, while Hurricane Georges of 1998 was a Category Two Hurricane when it hit the Florida Keys and the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

Category 3:

Hurricanes Roxanne of 1995 and Fran of 1996 were Category Three hurricanes at landfall on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico and in North Carolina, respectively.

Category 4:

Hurricane Luis of 1995 was a Category Four hurricane while moving over the Leeward Islands. Hurricanes Felix and Opal of 1995 also reached Category Four status at peak intensity.

Category 5:

Michael (2018-Oct-10, ca. 160mph winds; hit Florida’s Panhandle);

Maria (2017-Sep-18 until 20, ca.175mph winds; hit Puerto Rico, Dom Rep, Turks & Caicos Isl., Virgin Isl.);

Irma (2017-Sep-5 until 9, ca. 180mph winds; hit Caribean, Florida);

Matthew (2016-Oct-01, ca. 165 mph winds; hit Central America, Eastern United States up to Canada);

Katrina (2005-Aug-28-29, ca. 175mph winds; hit U.S. Gulf coast states and devastated New Orleans and the surrounding dams);

Ivan (2004-Sep-9-14, ca. 165mph winds; hit Caribean & U.S. gulf coast states);

Hurricane Mitch of 1998 was a Category Five hurricane at peak intensity over the western Caribbean. Hurricane Gilbert of 1988 was a Category Five hurricane at peak intensity and is one of the strongest Atlantic tropical cyclone of record.

Safety Rules and preparation for a hurricane

When your area receives a hurricane warning:

- Leave low-lying areas.

- Moore your boat securely or evacuate it.

- Protect your windows with boards, shutters, or tape.

- Secure outdoor objects or bring them indoors.

- Unplug electricial devices.

- Stay at home if it is sturdy and on high ground.

- Leave mobile homes for more substantial shelter.

- Stay indoors during the hurricane.

Other organizational preparations:

- Have cash and credit cards always handy.

- Fuel your car.

- Save several days’ water supply.

- Have enough batteries for your devices like radios

Hurricane WATCH

Hurricane conditions pose a possible threat to your area. In especially vulnerable areas, early evacuation may be necessary when a Watch is issued. Otherwise you should review hurricane safety procedures and make preparations.

Hurricane WARNING

Hurricane conditions are expected in your area within 24 hours. Areas subject to storm surge or tides should be evacuated as well as areas which could be isolated by flood waters. Follow the instructions of local officials. You will not be asked to leave your home unless your life is threatened.

A hurricane causes sea level to rise above normal tidal heights, with giant wind-driven waves and strong, unpredictable currents. These are the storm’s worst killers.

- Know your property’s elevation above mean sea level.

- Have a safe evacuation route planned.

- Learn the storm surge history for your area.

Tornadoes

Tornadoes spawned by hurricanes are extremely dangerous. When a hurricane approaches, listen for tornado watches and warnings, and be ready to take immediate shelter.

Hurricane Season – be prepared!

Enter the June-November season prepared.

Inventory boards, tools, batteries, nonperishable foods, and other emergency equipment.

Be informed!

Latest storm-related information will be available on NOAA Weather Radio and commercial radio and television.

Do not tie up telephone lines by calling local officials or the National Weather Service.

Listen carefully to broadcasters serving your immediate area.

Hurricane Emergency Plan

The National Weather Service advises following:

- Post emergency telephone numbers by the phone.

- Install safety features in your house, such as smoke detectors and fire extinguishers.

- Inspect your home for potential hazards (items that can move, fall, break or catch fire) and correct them.

- Have your family learn basic safety measures, such as CPR and first aid; how to use a fire extinguisher;

and how and when to turn off water, gas and electricity in your home. - Teach children how and when to call 911 or your local Emergency Medical Services number.

- Keep enough supplies in your home for at least 3 days. Assemble a disaster supplies kit. Store these supplies in sturdy, easy-to-carry containers, such as backpacks or duffle bags. Keep important documents in a waterproof container. Keep a smaller disaster supplies kit in the trunk of your car.

Disaster Supplies Kit Should Include:

- A 3-day supply of water (one gallon per person, per day)

- Food that won’t spoil

- One change of clothing and shoes per person

- Prescription medicines

- One blanket or sleeping bag per person

- First-aid kit

- Battery-powered NWR and a portable radio

- Emergency tools

- Flashlight, extra batteries

- Extra set of car keys and a credit card or cash

- Special items for infant, elderly or disabled family members

Official Website(s)

National Weather Service (Weather.gov)/ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Weather.gov

National Hurricane Center – NOAA

Federal Emergency Management Agency – FEMA

History: why where Hurricane Names introduced

For several hundred years many hurricanes in the West Indies were named after the particular saint’s day on which the hurricane occurred. Ivan R. Tannehill describes in his book “Hurricanes” the major tropical storms of recorded history and mentions many hurricanes named after saints. For example, there was “Hurricane Santa Ana” which struck Puerto Rico with exceptional violence on July 26, 1825, and “San Felipe” (the first) and “San Felipe” (the second) which hit Puerto Rico on September 13 in both 1876 and 1928. Tannehill also tells of Clement Wragge, an Australian meteorologist who began giving women’s names to tropical storms before the end of the l9th century. An early example of the use of a woman’s name for a storm was in the novel “Storm” by George R . Stewart, published by Random House in 1941, and since filmed by Walt Disney. During World War II this practice became widespread in weather map discussions among forecasters, especially Air Force and Navy meteorologists who plotted the movements of storms over the wide expanses of the Pacific Ocean.

In 1953, the United States abandoned as confusing a two-year old plan to name storms by a phonetic alphabet (Able, Baker, Charlie) when a new, international phonetic alphabet was introduced. That year, this Nation’s weather services began using female names for storms.

The practice of naming hurricanes solely after women came to an end in 1978 when men’s and women’s names were included in the Eastern North Pacific storm lists. In 1979, male and female names were included in lists for the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico.

The Retirement of Hurricane Names

Hurricanes that have a severe impact on lives or the economy are remembered by generations after the devastation they caused, and some go into weather history. The National Hurricane Center near Miami, Florida, monitors tropical disturbances in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific Oceans which could become a hurricane.

Whenever a hurricane has had a major impact, any country affected by the storm can request that the name of the hurricane be “retired” by agreement of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Retiring a name actually means that it cannot be reused for at least 10 years, to facilitate historic references, legal actions, insurance claim activities, etc. and avoid public confusion with another storm of the same name. If that happens, a like gender name is selected in English, Spanish or French for Atlantic Storms.

There is an exception to the retirement rule, however. Before 1979, when the first permanent six-year storm name list began, some storm names were simply not used anymore. For example, in 1966, “Fern” was substituted for “Frieda,” and no reason was cited.